The Economics of offering a Chemistry Degree

Chemistry seems like it’s in trouble in Universities, and a shared understanding of what’s going on might help develop some urgency about fixing that. This blog is intended to explain my understanding of the economics of teaching Chemistry in HE.

I’m working on this as part of my MA thesis, so if anyone wants to talk please let me know - it’s always helpful to hear other people’s perspectives. I’m developing it into a presentation, too, in case you are looking for a speaker to make everyone feel sad.

Crude Economics

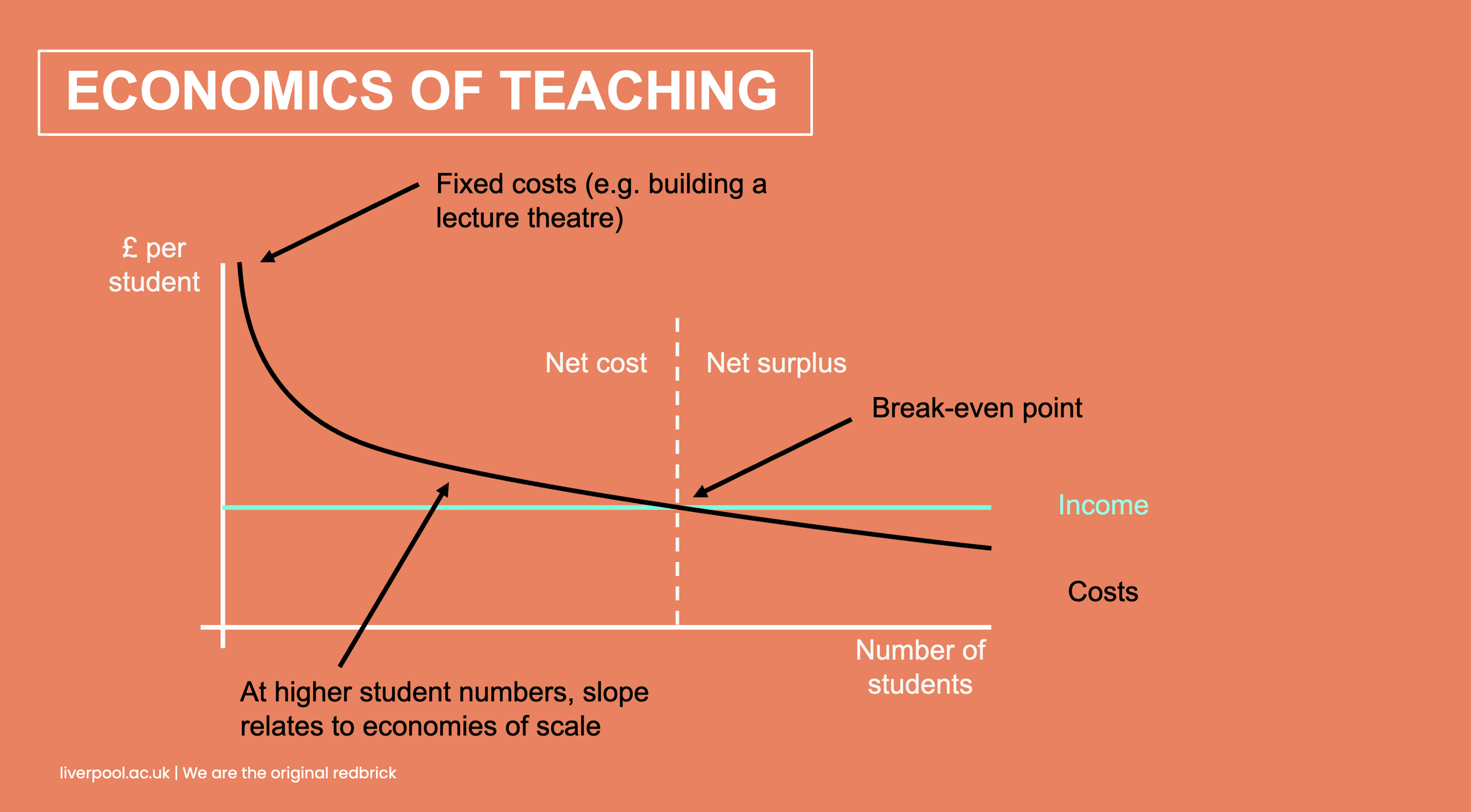

I have found data for per-student costs, so the central graph axes I am going to use are the £ per student and the number of students. Plotting costs for teaching gives some kind of line with a negative gradient. The y-intercept represents “fixed” costs (building a lecture theatre, paying staff, stocking a library), but these costs are a one-off spend which gets shared among more and more students along the x-axis. The “marginal” costs involved with teaching one more student are typically quite small once you’ve paid all the fixed costs (you need empty the campus bins a bit more frequently, you need an extra copy of a key text, you need another PhD student to do lab demonstrating this year). To a first approximation, per-student cost can be seen as progressive dilution of the massive fixed costs demanded by University teaching.

In undergraduate home teaching, the income per student is fixed. In England this is predominantly determined by the tuition fee, with a small top-up from the Government to acknowledge the high value of teaching. Scotland has a higher Government contribution but no fees for home students. The lines cross at some point, which can be seen as the number of students at which teaching breaks even. Having fewer students than this means that the subject costs a University money; having more means it generates income.

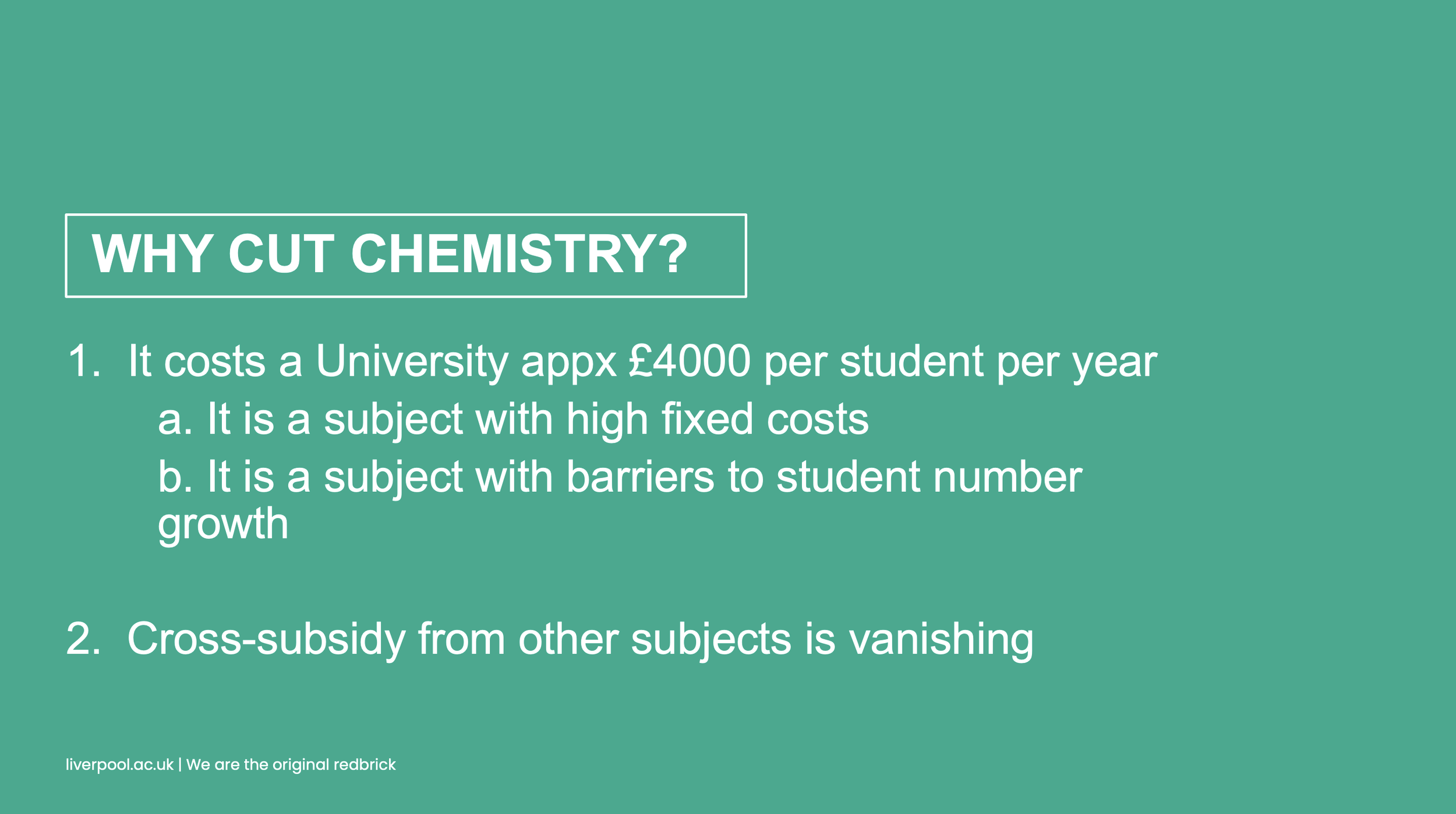

Where does Chemistry sit in this graph? 2019 work on TRAC costings by the DFE demonstrates that Chemistry sits below the break-even point on average in the UK: in 2025 numbers, each student cost a University about £4000 per year to teach. (Note that this analysis assumes that tuition fees rose with inflation to appx £11,500 in 2025, which they did not.)

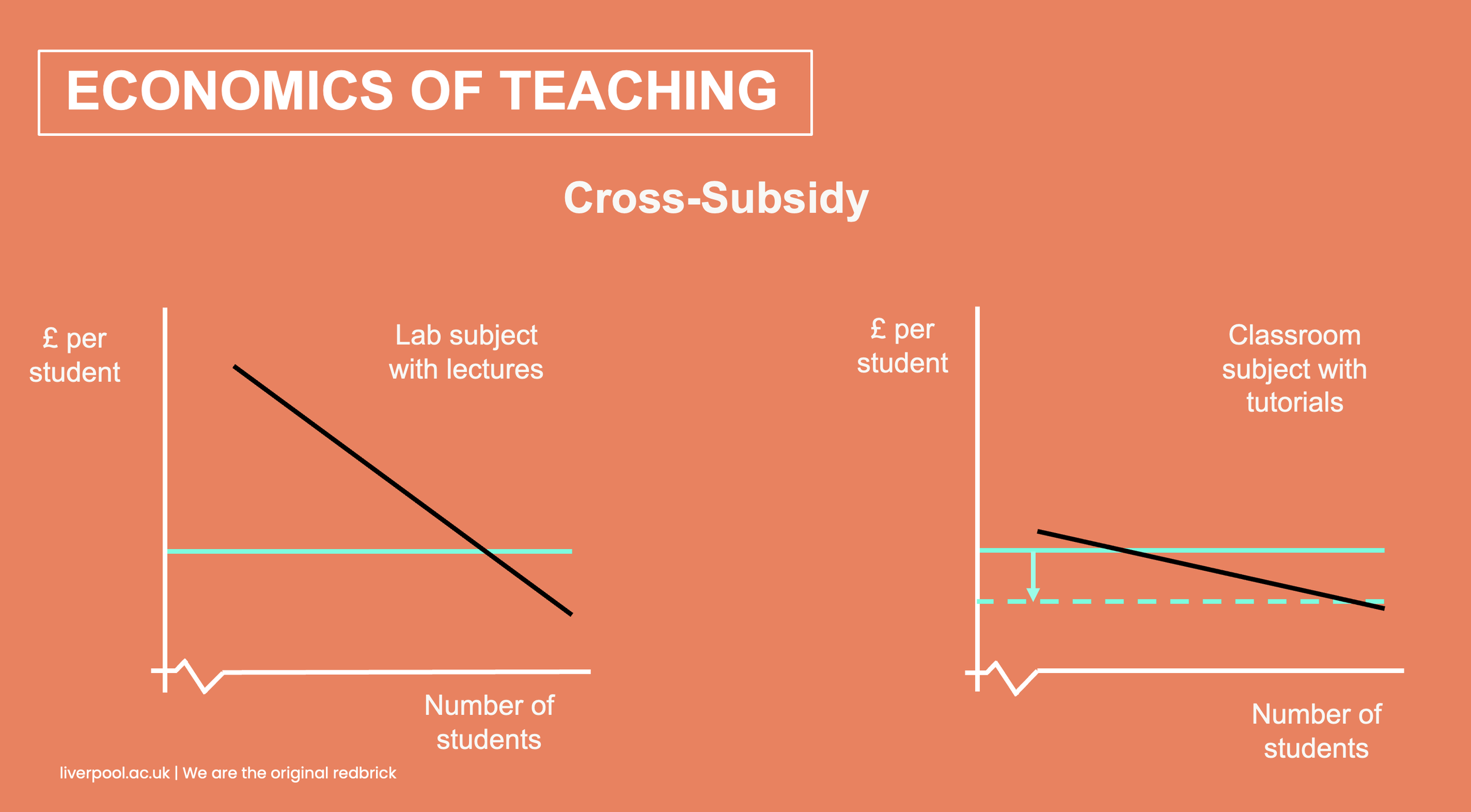

Universities are - by and large - charities. Surplus money is not going to greedy shareholders, but normally gets reinvested. This has generally served Chemistry well because its high subject-specific fixed costs (mainly building labs) make it difficult to return a surplus at moderate student numbers. Cheaper subjects can generate surpluses which subsidise our discipline, even when they use less cost-efficient pedagogies like tutorials.

The important feature of the last few years is that the income per student has not kept pace with inflation (dotted line in the right-hand graph). In real terms, this depressed income serves to increase the number of students at which a course breaks even. This is true of all subjects, but the proximate cause of the peril Chemistry is currently experiencing is the way that this has damaged the cross-subsidy mechanism: other disciplines can no longer pay for our subject-specific fixed costs.

One effect of inflation has led to greater pressure to recruit more students as this can shift the graph right, towards or even beyond the break-even point. But looking at the trend in Chemistry intake over the last 10 years suggests that the market is not growing - it seems unrealistic to project, say, a 10% growth in Chemists when the last decade has seen shrinkage of just over 5%.

This makes the recruitment game zero-sum: if a student gets recruited by one University, they are lost to another. The effect has been an incredibly ugly scrap. Universities are hungrier for students because inflation has damaged per-student income, but the cake has not grown. York eats, Hull starves. This is the rational outcome. If there were some unmet need for Chemistry teaching (like there seems to have been for Business Studies), this might not be true.

Having per-student costs and total student numbers allows us to do some very crude maths on the funding gap (£4k loss per student x 20k students): sector-wide, Universities subsidise Chemistry by about £80m per year. When people say things like “Government should fund the full cost of teaching Chemistry”, the number they are describing is probably approaching £100m per year with inflationary uplifts.

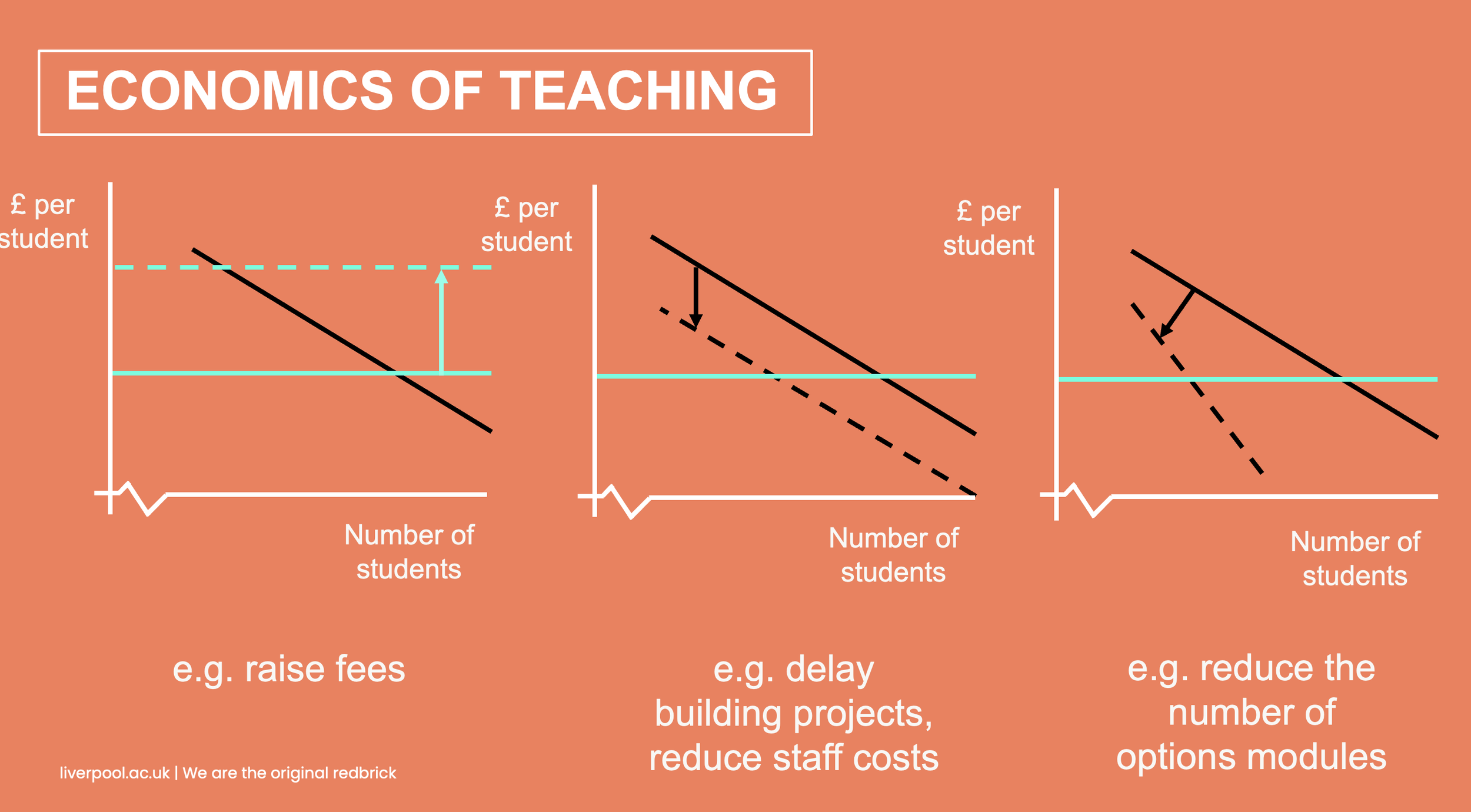

The diagram below looks at three ways of playing with the economics to hit a smaller break-even point, which explains a lot of Universities’ recent behaviour. On the left, an increase in income. Perhaps this is a governmental intervention on the fee level or boosting the level of high-cost subject funding, but developing MSc teaching and international recruitment are also ways of moving the green line up.

Lowering fixed costs (middle graph) can generally be accomplished by “sweating the assets”. You use a building for a few years longer than you had planned, you don’t replace staff who retire, you merge Departments into Schools to reduce admin costs. This can make for sad working conditions, though, something which directly affects the core missions of a University. It is perhaps a mark of how desperate the situation is that such measures are so commonplace at the moment.

The last option (right graph) is to try and alter marginal costs. Reviewing the curriculum can be one way to accomplish this, though this presents difficult tensions between economic and educational goals for the process.

Conclusion

So, why shut a Chemistry Department? Because it loses money and we don’t have cross-subsidies any more.

There are credible policy responses to this situation, but it’s worth stating explicitly that the current trajectory is to close small departments and grow large ones. Concentration is the only way that the fixed cost problem can be mitigated at a national scale as things stand.

It’s probably also worth stating descriptively that the current situation is closely related to the regulated market the UK has constructed. Government reduced its HE spending by burdening students with high fees, but then allowed that fee level to dwindle in value. The effect has been to marry the viability of high-cost subjects to the viability of the overall University system. Going beyond objective description, there are people who would argue that this is a market failure: Chemistry graduates are a great resource to society, but the imperfect structure of economic incentives encourages Universities to stop teaching Chemistry.

A competing hypothesis – and one which fully explains all the available observations – is that this situation is a market success. The market equilibrium is shifting and telling Universities that Chemistry is not sustainable. This is the reality that Vice Chancellors sit within when they decide to cut Chemistry. Whether or not they see a bright future for the subject, they need to keep the lights on in the library. They are responding rationally to the incentives they encounter, and the time horizons for their decisions are necessarily short.

What next?

My own conclusion from this pretty gloomy picture is that chemists need to make the case for Chemistry being a positive and hopeful part of Britain’s future. Make the case persuasively, make it persistently, and make it to government. “Sure it costs a bit, but can you afford not to invest in training Chemists?” We need to describe what is happening as a failure of the market model, rather than a success.

I honestly think we have everything we need to do a great job of this. This subject is an incredible training in thinking about substances and a fantastically broad education in understanding and communicating complex data: graduate chemists can do difficult things. Chemistry also links to large parts of the new Industrial Strategy extremely readily, and is one part of addressing high-priority Government problems. This is important when asking for money: perhaps £100m/year isn’t such a dreadful number when it gets compared with sums like £700m/year to address teacher recruitment/retention or £22b for carbon capture projects. We have thousands of academic scientists who make policy-aligned arguments like this routinely when applying for research grants. We have thousands of industrial scientists who can articulate how central graduates are to the work they do in foundational and cutting-edge sectors every single day. We just need to start getting them in front of the right people.