The Finances of Universities with Chemistry Departments

HESA produces data on University finances, and I thought it would be valuable to look at the Key Financial Indicators. The HE sector seems likely to enter a bleak time in the next few years, and I wanted in particular to see how the data related to Universities with Chemistry degrees.

Chemistry is an expensive subject to teach, so Universities which are illiquid or unsustainable are forced to ask whether they can continue to offer it. It is a very grim agenda, but I want to look for ways of anticipating financial problems so that it would be possible to identify and support Departments which might be at risk. The alternative is to begin responding after the closure has been decided.

This motivation was strengthened by the House of Lords report on the Office for Students, which criticized the weak focus on financial risk in the sector. Since the demise of HEFCE, the ‘market exit’ of departments is a stated aim of the UK HE system and the competitive environment means that closures (like Bangor in 2021) do not attract the levels of spontaneous professional solidarity which earlier closures (like Exeter in 2005) did. The cavalry is not coming.

Methodology

I used the 2023 Guardian League table to identify Universities with Chemistry degrees, then extracted the 2021-22 HESA finance data for those Universities. Heriot-Watt and Keele were not included in the HESA data, so I have omitted them. HESA explains that this absence is just due to a missed filing deadline.

The most important thing to note is that the numbers relate to the whole University, not their Chemistry Department.

Staff and Premises spending

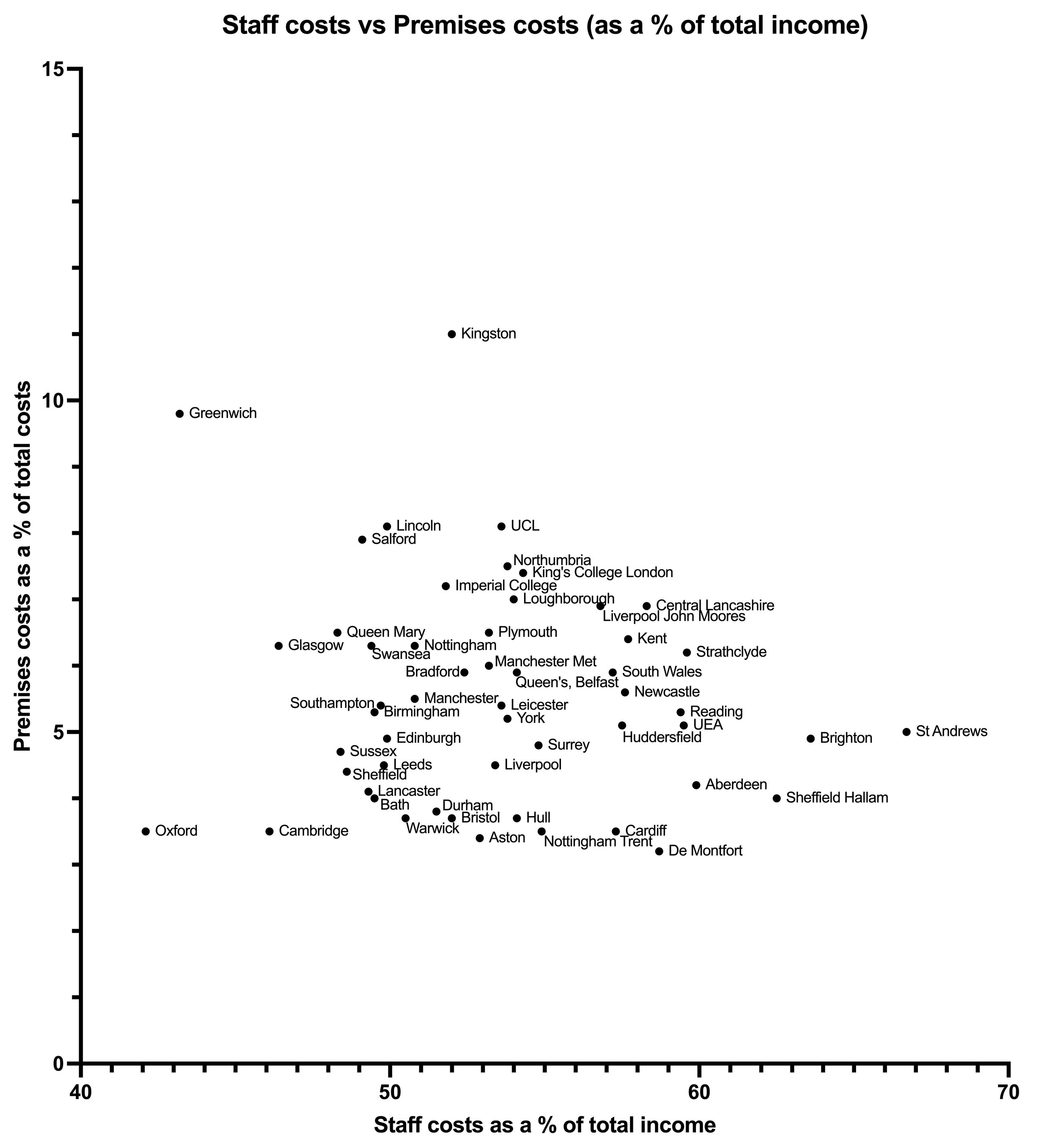

I’ve plotted the staff spend vs the premises spend as a proportion of total income. Premises costs seem to range mostly between 4% and 8% of total costs, while most staff costs sit in the 50%-60% window. The London Universities have high premises costs, with Oxbridge being low outliers on both axes (perhaps because of their high incomes).

As a % of total income, staff costs vs premises costs for Universities which have Chemistry Departments (2021-22 data)

The big message of this graph is to point out how different Universities experience different financial situations. Even if the absolute values are relatively similar, staff costs may seem reasonable in one place and unreasonable in another. Similarly, the expense of laboratory premises might seem bearable in one financial context and unbearable in another.

It will be interesting to see how the RAAC crisis plays out in these numbers; some Universities were building more intensively than others in the high tide of aerated concrete.

Liquidity Days

The liquidity days metric is a measure of how liquid a University is. It quantifies how many days an institution could survive using the cash and borrowing ‘on hand’ (but does not speak to other considerations like long-term borrowing). Liquidity is important for understanding whether minor bumps would trigger drastic action, and may be part of the picture in the discussion of interest rates when Universities seek (re-)financing.

The ‘liquidity days’ of Universities with Chemistry Departments (2021-22 data), loosely quantifying the number of days a University could subsist on cash and assets ‘on hand’.

The median liquidity time is about six months. In broad terms it’s probably good to have a high-enough number of liquidity days, but it’s also good to make full use of the money you have. I suggest that low liquidity is one risk factor for closing Chemistry Departments, but it isn’t clear to me what the ‘right’ level of liquidity is.

Surplus

Subtracting a University’s expenditure from its income gives you its surplus. There are subtleties about the calculation in the complex corporate structures of the modern University, but in broad terms sustaining a surplus for an extended period of time is what keeps a University from going bankrupt. Note that these are ‘snapshot’ figures, and may reflect unique events - it could be that some one-off cost puts a financially healthy University into the red for a year or two (again, RAAC will be an interesting thing to consider in this context).

As a % of total income, the surplus of Universities with Chemistry Departments (2021-22 data).

It’s possible to have a negative surplus if costs outweigh income, and some Universities with Chemistry Departments are in this situation. In my view, appearing low in this list for several years is another risk factor for the closure of Chemistry Departments.

When the threat is financial sustainability (rather than liquidity), the typical strategy is to cut Departments wholesale as structural funding problems can only be solved with structural changes to a University. Thinking - early and ruthlessly - about how to make sure the Chemistry Department survives the axe is a difficult but important problem to solve in such zero-sum situations.

Conclusion

Which perhaps brings me to my motivation for writing this blog in the first place. Saving Chemistry Departments will take some really careful strategising, and thinking about how to manage this is worth doing. Focusing the community’s efforts on a small number of Universities might be one practical way to do this.

Further Reading

The big arguments are covered well in The Great University Gamble by Andrew McGettigan, including a substantial discussion of infrastructure financing.

I’ve blogged before on student numbers, which have been an important component of University finances in the last decade. The erosion of the fee income by inflation perhaps makes this less significant in the near future; it will be interesting to see how Universities in England and Wales respond as teaching home students becomes loss-making.